Fashion City: How Jewish Londoners Shaped Global Style

Written by Nicholas Diamond-Krendel, co-founder of Luxury Leather Goods Brand Paradise Row

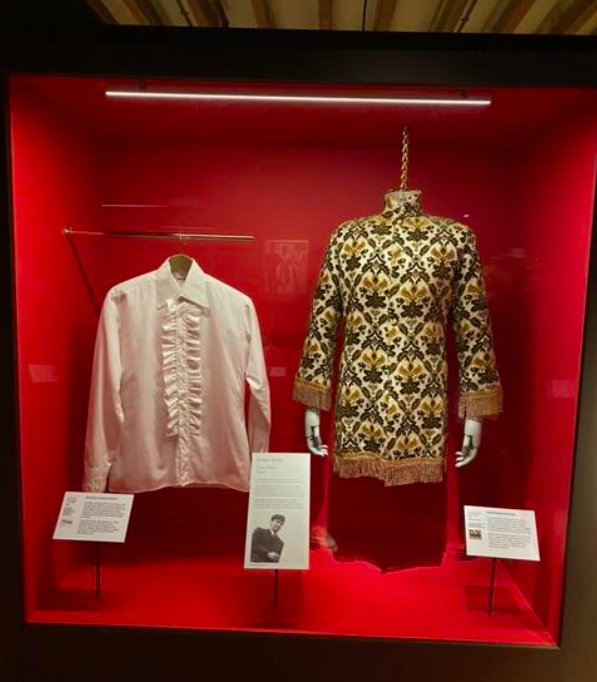

Source: Fashion City Wholesale Couture, Museum of London. Image shows the ‘wholesale couture’ part of the exhibition.

“What’s the difference between a tailor and a lawyer? A generation.”

So the old Jewish joke goes. The excellent new ‘Fashion City’ exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands follows the journey of amkho sher un ayren ('the simple people of the scissors and ironing board') from lives of hardship and privation as immigrants in the East End of London to the bourgeois respectability of West End couture and the fashionable boutiques of London’s Swinging Sixties.

But like the joke itself, such a characterisation seems strangely reductive, implying a clear trajectory when there was none, glazing over the individual tales of winners and losers, of independent designers and multi-store chains, of men and women, even Jews and non-Jews who are also part of this non-linear journey.

And that is where this exhibition excels. Michael Marks, Sir Montague Burton, Sir Phillip Green. These and many other august names of the Jewish shmata business are not the focus of this exhibition. Their stories have all been well told in Wikipedia entries and in the board minutes of their PLCs.

Instead, step forward Malka Fiszer (Anglicised to Millie Fisher in keeping with the widespread practice of Jewish migrants downplaying their roots to better assimilate into their host nation) who built up a successful umbrella business on Hanbury Street, only to find herself hostage to changing fortunes, losing her business and forced to pawn her wedding ring and even her bed.

There is the story of the unnamed tailor of Hoxton who, according to the experts and historians who brought this exhibition together, produced the finest bit of workmanship on display in the entire exhibition. There is no label on this simple blue three-piece suit, the craftsman’s legacy preserved only in each stitch and thread which endure.

Then there is the story of the Moldau family, the children of which came over on the Kindertransport to continue the leather goods business their family had built up in Vienna before the factory was seized and Aryanised after the annexation of Austria in 1938. The business flourished through the 1950s and 60s, producing under both its own Molmax label and for the likes of Harrods, Burberry and Liberty. In a particularly poignant revelation, I later discovered that this was the family of the exhibition’s own curator, Dr Lucie Whitmore, who had grown up unaware of her Jewish ancestry, her family, like so many others, uneasy talking about the events that had brought them to these shores.

Some of the most moving bits of the exhibition cover the interaction between Jews and other migrant groups, themselves part of their own similar and yet unique tale of displacement, reinvention and perseverance. The story of the East End is often told in successive but distinct waves of immigration, but here we have the snappy, pencil-moustached Jamaican, Winston Giscombe and Bengali couple Anwara and Ashab Begum, who supplemented their own income working for Jewish garment makers in Whitechapel, before starting their own businesses, some of which remain to this day.

There are sections on Moss Bros and Chelsea Girl (now River Island) as well as lengthy tributes to the likes of Cecil Gee, David Sassoon and Mr Fish as we move into the modern era; however, if the exhibition lacks one thing, it is perhaps a section on the present day. Where are these brands now? Of the ones which remain, how have they adapted to changing retail habits, the decline of the high street and the rise of a new generation of makers?

Only a few doors down from where the Fishers set up their feted umbrella shop on Hanbury Street is London Undercover, a contemporary umbrella store stocked across the world and founded in 2008 by a descendant of Jewish immigrants. Indeed my own journey as a fifth generation child of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants has taken me on the inverse journey to that described in this exhibition, moving from west to east London and from a respectable career in a multinational law firm to co-founding an independent luxury leather goods business, Paradise Row, just streets away from the house on Ford Square in Whitechapel where my great great grandparents had started out. And so the story continues…

But this is really to kvetch. The omission of contemporary brands as well as other iconic names of post-war fashion can easily be forgiven given the constraints of museum space. This is not the V&A or the RA, operating on comparatively minuscule budgets and within the constraints of a Grade I listed wharf building. Particularly skilful is the way the huge timber joists of this former warehouse have been repurposed into the ship through which you enter the museum, recreating the feeling of arrival experienced by successive waves of immigrants, the sense of foreboding, of not knowing what to expect, with only the possessions they could carry. Family testimonies are played over the speaker, a reminder of the precious oral tradition of immigrant stories handed down from one generation to the next.

And it is these videos which hint to a deeper purpose here. Remarkably, this exhibition started life not as an exhibition at all, but as a project to archive the previously dispersed collection of clothing, accessories and other ephemera in the Museum of London collection. Yes, there are gaps, but this somehow feels to miss the point. It is the ability to connect the exhibits to the precious oral testimony of what will be the last generation to have known these brands first hand that is the real achievement of this exhibition. Unlike so many of their family members left behind, the likes of Sophie Rabin, Netty Spiegel, Peggy Lewis, Otto Lucas and so many more will now be given their rightful place alongside more familiar names in the annals of British fashion.

My great great grandmother with my grandfather outside their house at 26 Ford Square, Whitechapel. Within a generation, the family was living on Portland Place in the West End.